Sound & Vision - Classic Video Technology (Part Two)

In the second of our two-part feature into legacy video technology, Tim Jarman tells the video disc player story…

Missed Part One? Click to read it now!

The ubiquitous DVD (Digital Versatile Disc) and BD (Blu-ray Disc) formats are such a common sight in most homes that it's hard to imagine life without them. Yet the early story of video disc technology was a surprisingly long and protracted one, with many technical challenges, market failures and vast financial losses along the way.

Manufacturers saw video discs as a simple way to distribute pre-recorded material, much like audio LPs. However, the public showed that they were not interested time and time again. A video cassette machine could make recordings from TV broadcasts as well as play commercial films, so it clearly represented better value. As a result, every one of the numerous types of video disc launched before DVD turned out to be an expensive commercial flop.

The idea of video discs is nearly as old as television itself. Since the crude 30-line transmissions of British TV pioneer John Logie Baird occupied a band of frequencies no wider than that carried by a sound-only radio broadcast, they could be recorded onto a 10-inch 78 RPM shellac disc of the same type used for music. Experiments started in the late nineteen twenties. Although technically feasible, the idea of 'Phonovision' disappeared, along with the 30 line system, in the mid-thirties. Neither was really good enough to be a popular home entertainment medium, and the first of many video disc formats had failed.

ON THE RECORD

It wasn't until the early seventies that the idea of video recording, using a stylus moving in a modulated groove cut into a disc, reappeared. Telefunken and Decca developed the 'TelDec' system, which used flexible plastic records which could each hold about twelve minutes of pictures and sound. The methods used to do this were collectively known as 'dense storage technology' and represented a significant step ahead from the conventional LP.

Telefunken TelDec player 1975: One of the first video disc machines to be offered to the public, but its short playing time meant it soon failed in the market.

To begin with, the TelDec groove moved the stylus up and down, rather than side-to-side, so the wasted space between the tracks was much less. FM recording was used, giving improved noise performance. The stylus that read the disc was sensitive to pressure (as opposed to position) and so could respond to a much higher range of frequencies. Its tip geometry had a gradual slope on the lead-in side and an abrupt step at its end; it was the pressure change as the disc passed this point that was measured to extract the disc's contents.

The TelDec disc stored one picture per rotation. The pickup was traversed across it by a mechanical geared linkage driven by the 'turntable' spindle; the disc, in fact, was driven by a small central hub while being supported against the stylus by a cushion of air. The groove density of this arrangement was 25 times higher than that of LP. As with almost every video disc format, an audio version was hinted at, playing at 8.25 RPM and giving two hours of top quality stereo sound per side.

TelDec's short playing time made it unattractive as a video format, however. Having to change the disc ten times to watch a feature film was impractical, and the promised automatic changer never appeared! A few machines were sold to the public under the Telefunken brand, but that didn't stop TelDec from being the first video disc to fail in the market, despite some interesting and impressive technology.

As the inventor of the first practical method for broadcasting and receiving colour TV, RCA certainly had the technical clout to develop a video disc format. Work had begun in the early nineteen sixties, and after some groundbreaking but ultimately fruitless work with holograms, a capacitive disc format was developed. The system's basic characteristics were finalised in 1978. By March 1981, the machines were ready for the public in the USA, heralded by what RCA claimed was the biggest product launch in business history.

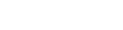

RCA SelectaVision CED 1981: The CED system offered good picture quality and stereo sound but was a business disaster that generated enormous losses for RCA.

The SelectaVision CED (Capacitive Electronic Disc) used a 12-inch double-sided plastic disc with a spiral groove housed in a sealed caddy, necessary to exclude dirt and give reliable operation in the domestic environment. The disc spun at 375 RPM, and each side contained up to 75 minutes of programme time for the UK version, but the 60Hz frame rate of American TV meant 450 RPM was required there, reducing the playing time to a maximum of 60 minutes per side. This led to two discs sometimes being required to hold a full-length feature film which would easily fit on a single video cassette.

The groove density of a CED was around forty times higher than that of a standard LP, but unlike an LP, the groove was plain and unmodulated – it served only to guide the stylus. Video and sound information was encoded by the varying electrical capacitance between the stylus tip and the disc, this being a factor that could change far more rapidly than the physical movement of a stylus tip ever could. Linear tracking was used, with a long stylus cantilever serving the place of a conventional pivoted arm. Deflections in the cantilever instructed the player's servo system to move the carriage along as required.

The groove density of a CED was around forty times higher than that of a standard LP, but unlike an LP, the groove was plain and unmodulated – it served only to guide the stylus. Video and sound information was encoded by the varying electrical capacitance between the stylus tip and the disc, this being a factor that could change far more rapidly than the physical movement of a stylus tip ever could. Linear tracking was used, with a long stylus cantilever serving the place of a conventional pivoted arm. Deflections in the cantilever instructed the player's servo system to move the carriage along as required.

Direct drive for the 'turntable' (in practice, a small hub and clamp arrangement in the centre) made the CED drive the equivalent of a state-of-the-art conventional turntable of the day. The capacitive system could store colour pictures and stereo sound, along with extra digital information which told the player if the recording was mono, stereo or dual language and frame number data for some of the more advanced players' search systems to use. Picture quality was broadly similar to that offered by a quality video cassette machine, but the sound was notably better until hi-fi stereo sound became available on the VHS and Beta systems.

The first CED players appeared in the UK in late 1983, produced by Hitachi. They were keenly priced, but CED was a commercial disaster. RCA abandoned making players in 1984 and would eventually lose a reputed $580 million as a result of the project. Hitachi made players for a little longer, and disc production continued until 1986, after which the whole sorry affair came to a close.

JVC's VHD (Video High Density) system appeared on the market in 1983, and like CED, took the form of a capacitive disc stored in a caddy. However, the 10-inch plastic discs were grooveless. So instead, the stylus was guided by electronic signals encoded within the recording (a similar method to that used in the 'Dynamic Track Following' technique of the Philips V2000 video cassette system). This allowed for improved search, pause and skip functions without damage to the disc, and the system showed much promise.

JVC XL-V1: JVC's focus on its VHD and AHD systems put it at a disadvantage when the Compact Disc was announced. Its first player, the XL-V1, was therefore just a re-packaged Hitachi DA-1000.

UK market leader Ferguson showed interest in the VHD system, having enjoyed considerable success with JVC's VHS video cassette machines. Prototype players in Ferguson livery were produced, and parent company Thorn went as far as to set up a factory in Swindon to press the discs. However, the system was never released on the British market, and the facility ended up being surplus to requirements. Thorn also had plans to put VHD video jukeboxes in pubs, but this too came to nothing.

VHD had an audio offshoot as well. AHD (Audio High Density) reflected the interest in using high capacity video formats to create a system with improved audio performance and longer playing time to replace the conventional LP. This failed too, but more importantly, it diverted JVC's resources from work on the more important audio Compact Disc. Therefore, the company started the CD race from behind, initially lacking a player of its own design. Instead, it marketed a rebadged version of the Hitachi DA-1000, a humiliating position for a company of JVC's stature. The system's good search and still facilities found some niche applications in Japan, but VHD was never sold as a consumer product outside its homeland. JVC abandoned it in 1987, with disc production stopping in the early nineties.

GETTING CLOSER

It was Philips that made the greatest impact on the video disc market in the analogue TV era. From 1972 onwards, it had shown pictures of and demonstrated various prototype machines for a format that was at first known as VLP (Video Long Play). Always compact and stylish, the VLP system was set apart by its use of a laser beam to read a gleaming silver disc, again double-sided and 12-inches in diameter. Contactless optical readout guaranteed no wear on the recording, which could be sealed in clear plastic for almost complete protection. However, lasers were still a developing technology in the early seventies. The miniature semiconductor laser found in the CD players of the next decade was still not a practical proposition for mass production.

Philips prototype VLP player: Throughout the 1970s, Philips showed pictures of its VLP videodisc player. They were portrayed as neat, attractive and convenient machines.

Therefore, the first VLP players used a helium-neon laser tube, a powerful device requiring elaborate controls and a high voltage power supply. This component was still in place when the system, known by this stage as LaserVision, was launched in 1979 in the USA and 1980 in Europe. The first two players available in the UK were dubbed the VLP 600 and VLP 700, in deference to the format's original name. Both were identical, except that the VLP 700 included a remote control. The picture and sound quality of Laser Vision were excellent, approaching that of studio equipment.

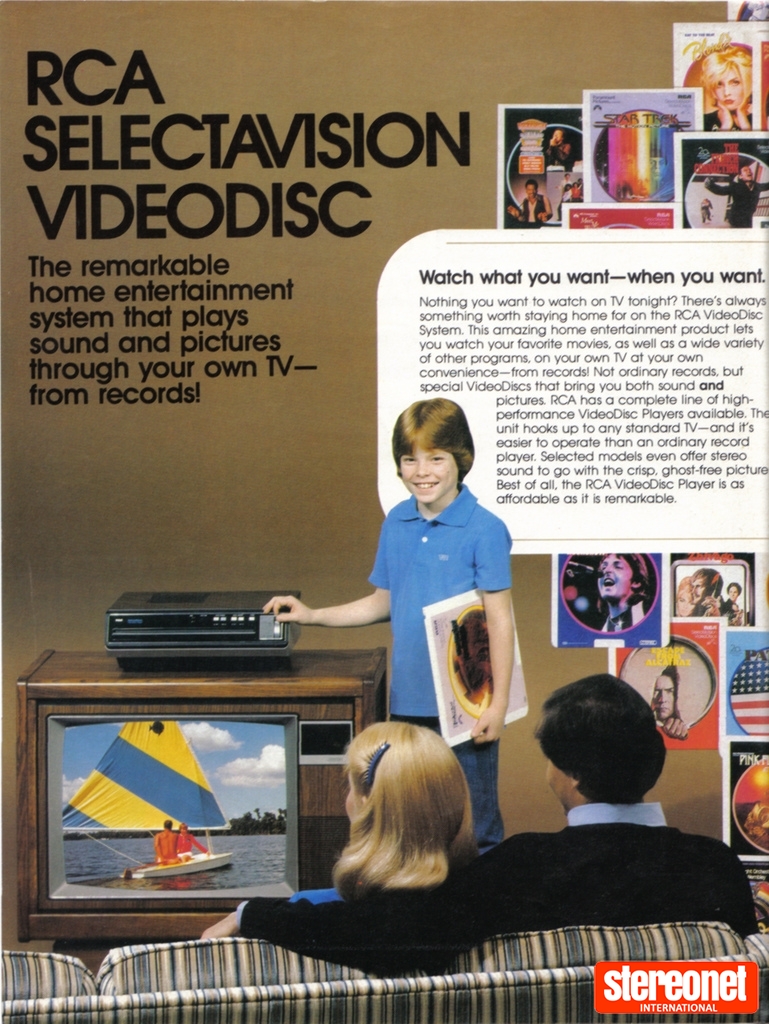

Philips Laservision disc: The gleaming 12-inch silver disc which formed the basis of the LaserVision system.

Also, the discs had been carefully designed, with two types being produced. Feature films were recorded using a method known as 'long play', here as much playing time was crammed onto the disc as was possible. The technical term for this was 'constant linear velocity', where the same amount of information was passed across the laser beam in a given time regardless of whereabouts on the disc it was located. This required that the disc ran faster when playing material near its centre than it did for that situated at its edge, a similar method to that employed for audio CDs.

The other type of LaserVision disc was called 'active play', which was used for material of an educational or interactive nature. Active play discs were recorded with two TV frames per revolution and therefore were played at 'constant angular velocity' like a conventional audio LP. Because of this, the laser beam could be made to jump tracks at the interval between the frames, allowing for perfect stills and seamless skips between programme sections.

Philips VLP 700: One of the most popular LaserVision players. Also, note the Philips Motional Feedback loudspeaker in the background, another product of advanced Philips research during the 1970s.

Despite its technical excellence, LaserVision was not a great success. At a time when video cassette recorders were in great demand, it was only ever a niche product despite a good supply of material and, latterly, some aggressively competitive pricing. An attempt to inject some life into the format was made in 1986 when it was announced that an updated version of the Domesday Book was to be produced to mark the 900th anniversary of the original. This was to be recorded on two LaserVision discs and made available in many British schools, complete with a special player and computer system to access the information. Sadly, the project was not successful, with the computer equipment proving to be temperamental in service. It was quietly withdrawn when the computers became outmoded, and recent efforts to recover the data from the discs have proved to be far from straightforward. Books: 1 Computers: 0!

SUCCESS AT LAST

It was Pioneer that saved LaserVision with its LaserDisc format, known as LD in Japan. This retained the picture encoding of the Philips original but replaced the analogue FM soundtrack with a digital one, similar to that used in CDs. Pioneer LaserDisc players could play the original Philips discs, but an early Philips player could only play the new recordings without sound. Many of the new Pioneer machines could also play audio CDs, helping to give potential purchasers additional confidence. Should the format fail, the owner would at least still have a decent CD player for their money.

LaserDisc made some progress in Japan and the USA, where it was popular with serious movie fans who wanted to build up a durable library of their favourite material. Bigger screen sizes had shown the limitations of video tape, and the digital soundtrack gave impressive performance; discs continued to be issued until the advent of DVD. LaserDisc marked the end of the analogue video disc era but showed that video discs could be practical, reliable and popular – particularly in Japan. So even if it wasn't a global success, it was far from a flop.

You might say that it paved the way for DVD, which was what the world was waiting for. A mercifully brief format war surrounded its launch, but it soon became the industry standard, and the world was now watching and buying digital video discs in vast numbers. Without all the failed formats that came before it, DVD would arguably not have happened when it did or how it did. Each failure advanced the art of recording, electronics and materials technology, and any of them could have formed the basis for a vastly improved replacement for the LP.

One could argue that were it not for the techniques developed for LaserVision, the Compact Disc system would have taken many years more to appear. Moreover, without LD, there is a strong possibility that some sort of FM encoded analogue disc for audio (such as AHD) would have emerged in the early eighties, tying the industry to a non-portable and non-car playable medium for another decade. For all their failures then, the world's great electronics companies got it right in the end.

Missed Part One? Click to read it now!

Tim Jarman

An engineer by profession, Tim Jarman is one of the UK’s leading classic hi-fi writers, repairers, restorers and collectors. There’s little he hasn’t got his teeth into over the years – from breathing new life into obsolete VCRs to reverse engineering and recoding the microprocessor of a classic B&O Beomaster 8000, his subject knowledge is vast.

Posted in:Home Theatre Visual

JOIN IN THE DISCUSSION

Want to share your opinion or get advice from other enthusiasts? Then head into the Message Forums where thousands of other enthusiasts are communicating on a daily basis.

CLICK HERE FOR FREE MEMBERSHIP